How Justice Scalia could become the savior of public employee unions

Organized labor is on tenterhooks these days over a pending Supreme Court ruling that could spell life or death for public employee unions.

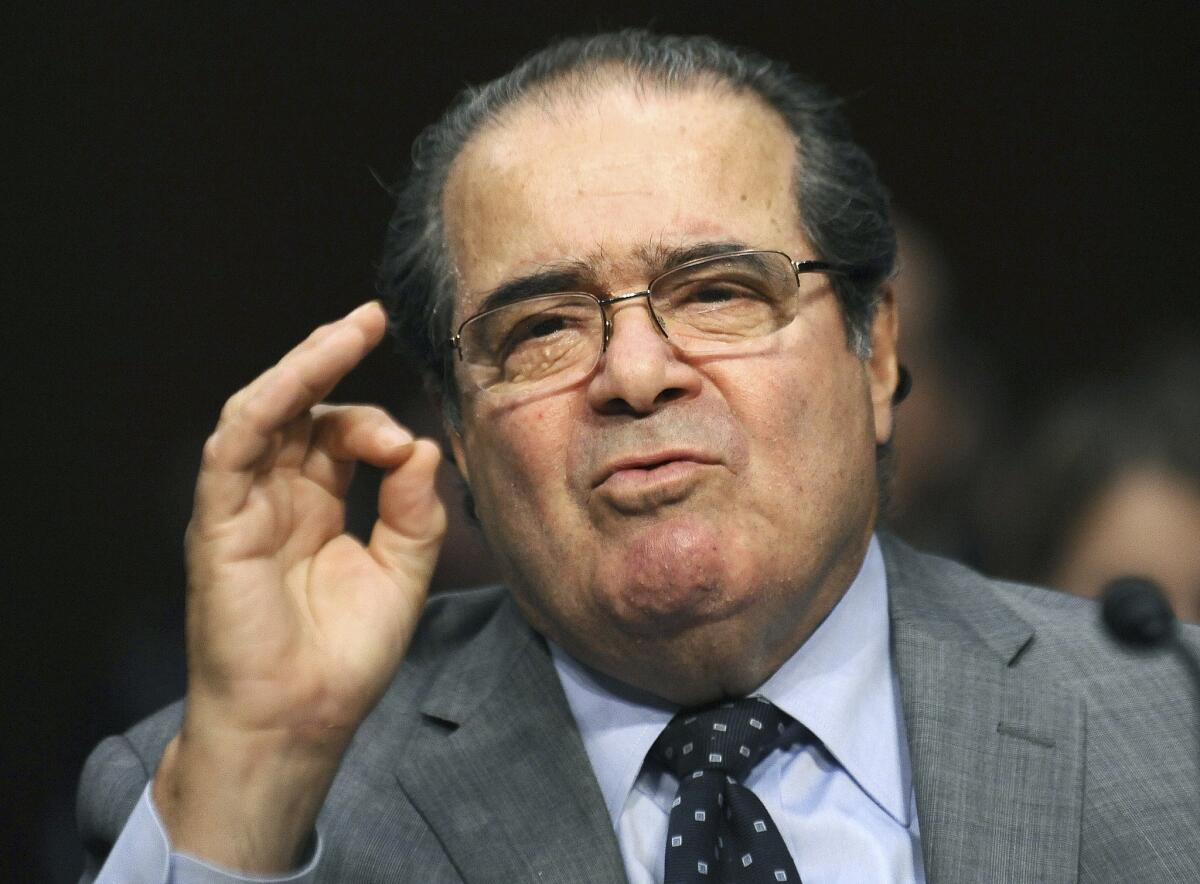

What makes this a man-bites-dog story is the identity of the man who might save public employee unions from extinction: The reliably conservative Justice Antonin Scalia.

Here’s the background of Harris vs. Quinn, on which a ruling is expected from the court any day now.

The roots of the case date back to 2003, when the Illinois Legislature designated some home healthcare workers public employees and allowed them to organize through the Service Employees International Union. They didn’t have to join the SEIU, but those who didn’t still had to pay an “agency fee” to the union to cover its expenses in negotiating and administering contracts.

That’s a common arrangement in many states, including California. It’s based on the principle that the public employee unions are compelled by law to represent members and non-members alike, so the latter should pay some of the costs of representation.

Agency fees, which can’t be used to fund political activity, have been upheld by the court since a 1977 precedent-setting decision in Abood vs. Detroit Board of Education. In a 1991 case, the principle got a ringing endorsement from Scalia himself, who wrote that “where the state creates in the nonmembers a legal entitlement from the union, it may compel them to pay the cost.”

In April 2010, the Illinois law was challenged by a group of home-care workers who argued that being forced to pay anything to a union infringed on their free-speech rights. Their cause was taken up by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, an anti-union group that expanded the case into broad challenge to the Abood decision and muscled it onto the court’s docket.

If Abood is overturned, that could be a death blow to public employee unions, which would lose an important source of income.

Not only the SEIU and other unions have stepped up to defend the precedent before the court. So have the federal government and eight state attorneys general, including California’s Kamala D. Harris. The states argue that collective bargaining helps maintain pay, professional standards and training programs for these chronically overlooked workers in ways that can’t be done through state administration alone.

During oral arguments in January, Scalia sounded a strong note against the main argument of the Right to Work Foundation. He didn’t buy the foundation’s assertion that public employee union activity is inevitably more about advancing political goals -- and therefore an infringement of the free speech of workers who disagree with those goals -- than improving workplace pay and conditions. Just because those conditions are matters of “public concern,” Scalia argued, doesn’t turn them into political issues. The key exchange between Scalia and the Right to Work lawyer is here.

Scalia’s words have alarmed anti-union conservatives. The day after oral arguments, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial writers fired a shot across his bow. “We’d hate to see such a stalwart supporter of the First Amendment as Justice Scalia join the liberals,” they wrote.

But the precedents in Scalia’s own jurisprudence are clear. First Amendment rights aren’t at issue in Harris vs. Quinn. If he follows his own stated principles, he’ll be turning the right-to-work crowd away.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.