How Uber’s big settlement may make things worse for its drivers

- Share via

If there's one thing the ride-hailing company Uber has become great at, it's identifying legal threats to its business model. That's the reality behind its $84-million settlement Thursday of two federal class-action cases brought by drivers. The cases could have forced Uber to classify its drivers as employees, not independent contractors, a change that could impose billions of dollars in costs on the company, eroding its potential profitability and its supposed value.

The deal covers about 385,000 drivers, who pay their own expenses while serving passengers sent their way via Uber's mobile phone app. Uber sets the fares, regiments much of the drivers' work activities and behavior, and takes more than 20% off the top. The lawsuits asserted that these conditions make the drivers tantamount to employees, despite Uber's contention that they're free to drive when and where they choose.

If we had not settled, there were some serious risks that all we have fought for - and have achieved - could be taken away.

— Shannon Liss-Riordan, attorney for Uber drivers

The settlement, which could rise to $100 million if Uber goes public at a valuation well beyond its current private market value of more than $60 billion, doesn't resolve whether the drivers are employees. Other lawsuits over that issue are pending, as well as union initiatives and an investigation by the National Labor Relations Board. The settlement does, however, underscore that litigation can be a thin reed for workers trying to redress inequities in the workplace. It's expensive and time-consuming, and the outcome anything but certain.

"If we chose not to settle this case, we faced risks,” said Shannon Liss-Riordan, the attorney for the drivers, in a prepared statement. Among these was “the risk that a jury in San Francisco (where Uber is everywhere and quite popular) may not side with the drivers over Uber." Liss-Riordan also seemed to be rattled by a recent ruling by a federal appeals court in San Francisco that placed the class designation in one of the two cases under new scrutiny, with the possibility it could be overturned. (The second case was filed in federal court in Boston.)

See the most-read stories this hour >>

"If we had not settled," she said, "there were some serious risks that all we have fought for - and have achieved - could be taken away." She added, "Importantly, the case is being settled - not decided. No court has decided here whether Uber drivers are employees or independent contractors and that debate will not end here." We've reached out to Liss-Riordan with questions about the deal, and will update if we hear back.

The key question left unanswered by the settlement announcement is whether the drivers are receiving enough in return for what they're giving up. As is often the case with class settlements, the big headline number obscures how little trickles down to the plaintiffs. In this deal, drivers with the most time and mileage recorded with Uber are in line to receive one-time payments up to about $8,000. The typical driver, however, will receive far less from a settlement pool that averages out to $218 per driver.

Nothing fundamental in the balance of income and expenses will change as a result of the deal--drivers will still be on the hook for gas, insurance and wear-and-tear on their vehicles, and Uber will retain the right to set fares and extract fees and commissions of more than 20%.

Yet settlement of the cases is surely a good deal for Uber by removing what it plainly regarded as a massive threat. Had the litigation continued, it might have put the company's entire business model on trial, exposing the degree to which the economic benefits of the so-called "gig economy" flow heavily, even exclusively, toward investors and executives at the expense of those providing the core service. The lawsuits were closely watched by other companies profiting from "independent contractor" labor, including fast-food restaurants, which are also fighting off NLRB initiatives to force them to give workers the full panoply of rights as employees, including better pay, benefits and working conditions. Settlement of the case could vastly reduce the leverage of worker advocates and government agencies alike to reduce the exploitation of "non-employee" workers.

Uber is portraying the deal as an unalloyed victory -- for drivers. According to a statement issued over the name of Uber CEO and co-founder Travis Kalanick, "drivers value their independence — the freedom to push a button rather than punch a clock, to use Uber and Lyft simultaneously, to drive most of the week or for just a few hours."

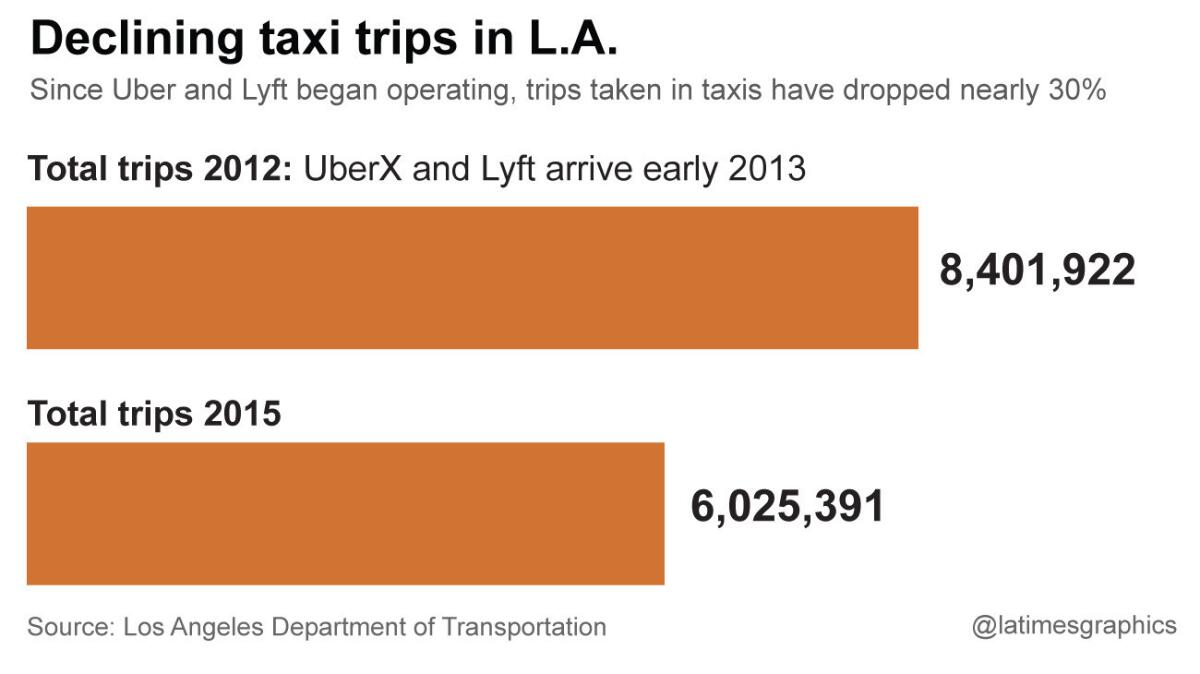

Yet that glosses over indications that working conditions under Uber and similar firms such as Lyft aren't as liberating as the firms say. While the ride-hailing services have reduced transportations costs for passengers, they've devastated incomes for taxi drivers, many of whom have signed on with Uber and Lyft because they have no alternative. Since the arrival of Uber and Lyft, taxi trips in Los Angeles have fallen by nearly 30%, as my colleague Laura Nelson reported last week. In San Francisco, the headquarters of both firms, the decline has been more than two-thirds.

This has taken a toll on drivers' incomes, reducing take-home pay to as little as $400 a week, down from $800 a few years ago, Paul Ezadjian, a manager for LA Checker Cab, told Nelson. “For a consumer, Uber is very good,” he said. “But for the driver, it's very bad.”

Thursday's announced settlement, which must still be approved by a federal judge, moderates some of the regimentation Uber imposed on its drivers via its mobile app. It eliminates Uber's ability to "deactivate" drivers -- the equivalent of firing them from the service -- at will, requiring instead a showing of "sufficient cause" and a delay to give drivers a chance to rectify shortcomings. Among other restrictions, Uber will no longer be permitted to deactivate drivers for failing to accept enough rides. The firm will establish an arbitration procedure for drivers threatened with termination.

Uber also will allow drivers to solicit tips from passengers, who often are unaware that tips aren't included in their fares. Drivers will be permitted to place signs in their cars stating, "tips are not included, they are not required, but they would be appreciated."

Finally, the settlement requires Uber to "facilitate and recognize" drivers associations. According to Liss-Riordan, these will be able to "bring drivers' concerns to Uber management, who will engage in good faith discussions (on a quarterly basis) regarding how to address these concerns." Whether this is a greater benefit to drivers than to Uber is unclear, given that established unions already have been mobilizing to organize Uber drivers -- a development that the NLRB is trying to assist by investigating whether the drivers should be classified as employees.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

The settlement still leaves Uber with great latitude to regiment its labor force in ways documented several months ago by Luke Stark of New York University and Alex Rosenblat of Data & Society, an independent research institute. "Through Uber’s app design and deployment," Rosenblat explained in the Harvard Business Review, "the company produces what many reasonable observers would define as a managed labor force."

Among other advantages enjoyed by the company, it sets the rates: "Uber has full power to unilaterally set and change the fares passengers pay, the rates that drivers are paid, and the commission Uber takes." Uber has the power to manipulate work schedules via "surge pricing," which raises fares at certain times and places to encourage an inflow of available drivers.

"Some drivers referred to surge as a “'herding tool' that ushered them into specific geo-fences," Rosenblat reported. "Our research, however, found that the promise of higher wages from surge pricing is often unreliable."

In short, the Uber settlement gives drivers a few dollars as a one-time payout but still leaves them working as Uber employees in all but name. Since these lawsuits had the potential to force real improvements in the drivers' conditions and rebalance the flow of profits from their efforts, it's hard to see this as their victory.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik's blog.

ALSO

What you need to know about the Uber settlement

Volkswagen to take $18.2-billion hit on emissions scandal

Uber will pay up to $100 million to settle suits with drivers seeking employee status